Ask a MoFo: An Overview of Traditional Venture Capital vs. Corporate Venture Capital

Early-stage investors can materially influence the strategic direction of the startup companies that they invest in. Because of that, investors and founders alike should be aware of the unique incentives and goals of different types of investors and take those into account when fundraising.

There are many sources of capital available to fast-growing startups. The two main investor groups are traditional venture capital firms (“VCs”) and the venture capital arms of established companies, known as corporate venture capital funds (“CVCs”). In general, VCs and CVCs are similar in many respects (in that they seek to invest in promising startups), but they also can have fundamentally different incentives and expectations. Generally speaking, VCs prioritize financial returns, while most CVCs prioritize strategic or commercial objectives. This article provides an overview of the structures and incentives of these two investor groups and outlines certain relationship dynamics to consider during the fundraising process.

Traditional Venture Capital

A traditional venture capital firm raises money from third parties (limited partners), pools it together in one or more investment funds, and seeks financial returns over a defined investment period, commonly ranging from 8 to 12 years. VCs charge investors in their funds a management fee, generally equal to 2% of the fund’s committed capital (intended to cover operating and personnel costs), and a performance fee/carried interest, generally equal to 20% of the profits generated by their investment activities (intended to reward good investment decisions). This structure incentivizes VCs to make high-risk, high‑reward investments in the hopes that a few explosive wins will more than offset a high number of modest losses. This means that they typically prioritize disruptive, differentiated technologies, aggressive growth strategies, and business models that can support a high return on investment. VCs tend to source prospective investment opportunities through prior teams they have worked with, referrals, networking events, pitch days, and other methods.

Corporate Venture Capital

CVCs are investment arms of established companies. Many CVCs are focused principally on strategic and commercial considerations—while financial returns tend to still be important to CVCs, they are often secondary to broader strategic and commercial objectives.[1] A typical CVC strives to gain a competitive advantage by identifying promising new technologies to complement or enhance the business of its parent company through establishing commercial arrangements, forming partnerships, and/or acquiring startups. Investments can allow a CVC to, among other things, obtain deeper insight with respect to new technologies, gain exposure to new talent, enter new markets, enhance the parent company’s business, and identify potential acquisition targets. Capital for CVC investments comes from the balance sheet of its parent company, so CVCs are not accountable to third-party limited partners and generally do not have strictly defined investment periods. This allows CVCs to consider a potentially broader set of investment opportunities over a potentially longer investment timeline and remain active in economic downturns when VCs may be slower to deploy capital. However, it also means that a CVC’s investment focus or level of capital deployment may shift over time as the strategic priorities or financial fortunes of its parent company change. CVC investors tend to be in the same (or a closely related) industry as the startups in which they invest and may even be an existing or potential customer or supplier.

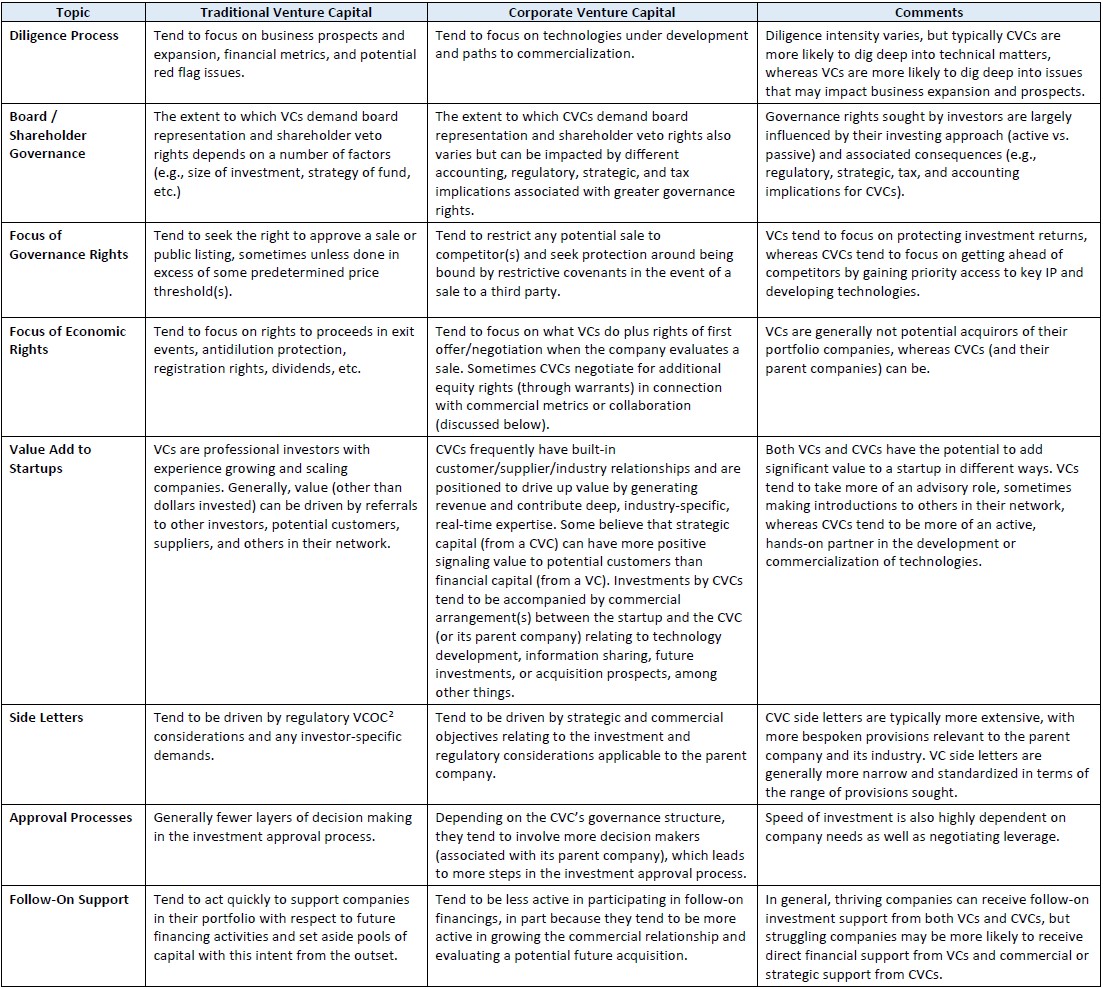

Below is a high-level summary of considerations to keep in mind when raising money from a VC vs. CVC firm:

Conclusion

When fundraising as a startup or deploying capital as an investor, it is important to consider the motivations of new investors, who may encourage the company to, for example, (a) take large risks to become the next unicorn and go public (a potential aim of VCs) or (b) make technological advances in a field and be acquired by an insider (a potential aim of CVCs). Evaluating any prospective investor’s ultimate objectives, motivations, and additional value-add (beyond a check) is critical to ensuring strategic alignment across a fast-growing company’s shareholder base.

[1] This, of course, is a spectrum. Not all CVCs are strategic in nature—CVCs that are geared more toward a high return on investment generally act similar to traditional VCs. For purposes of this article, we use the term CVC as generally synonymous with “strategic” CVC firms, but the goals and incentives of any CVC should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

[2] VCs may require certain management rights in their portfolio companies in order to qualify as a “Venture Capital Operating Company,” which provides VCs with certain exemptions from regulatory requirements. See our article.

Receive invites to MoFo startup events and legal updates

ScaleUp

Legal Guidance for Startups